- Home

- Leah Purcell

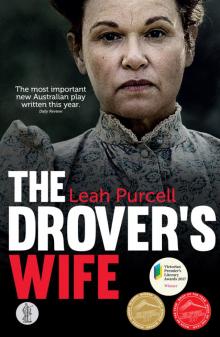

The Drover's Wife

The Drover's Wife Read online

LEAH PURCELL is a proud Goa-Gunggari-Wakka Wakka Murri woman from Queensland. She is an actor, writer and director. Her directing credits for Belvoir include Radiance (in which she also starred), Brothers Wreck and Don’t Take Your Love to Town (which she also co-adapted and starred in). Her other theatre credits as an actor include, for Belvoir: The Dark Room, Stuff Happens, Parramatta Girls, The Marriage of Figaro, Box the Pony (which she also co-wrote); for Bell Shakespeare: King Lear; for STC: Blood Wedding; and for Griffin: The Story of the Miracles at Cookie’s Table (with HotHouse Theatre). Leah co-directed season one of the acclaimed ABC series Cleverman and has just completed directing a new 7 Network/Screentime series, The Secret Daughter. She is also known for her writing and directing across Redfern Now (series one and two), the children’s TV series My Place, and the award-winning short films She.Say and Aunty Maggie and the Womba Wakgun. Her film and TV credits as an actor include Janet King, Black Comedy, Mary: The Making of a Princess, House of Hancock, Love Child, Last Cab to Darwin, The Darkside, My Mistress, Jindabyne, Lantana, Redfern Now, The Proposition, My Place, Love My Way, Starter Wife and Police Rescue. She is the best-selling author of the anthology Black Chicks Talking, which was turned into an IF Award-winning documentary. Leah’s other awards include the 2014 Balnaves Foundation Indigenous Playwright’s Award, a 2013 AACTA Award for Best Female Actor in a TV Drama, a Helpmann Award for Best Female Actor, Matilda Awards for Best Actress and Director, a Film Critics’ Circle Award, an IF Award, two Actor of the Year and one Singer of the Year Deadly Awards, the inaugural Bob Maza Fellowship, and the prestigious Eisenhower Fellowship for her artistic endeavours, community philanthropy and cultural activism. Leah is a proud member of Actors Equity.

‘Leah Purcell has made a bold and exciting contribution to Australian playwriting and, arguably, to Australia’s identity. She has repurposed colonial tropes and reinvented an existing form to insist that we consider a new exploration of culture … This is a work to challenge our sense of ourselves and of our place.’ — NSW Premier’s Literary Award judges’ comments

‘This re-imagining of a classic Australian short story explodes out of the blocks with a moment of stark brutality and never lets up … Relentless in its trajectory, neither characters nor audiences are let off the hook as the piece drives towards two heinous acts of violence, and then beyond them, into the beginnings of something other. The Drover’s Wife subverts, re-inspects and interrogates our histories through powerful storytelling.’ — Victorian Premier’s Literary Award judges’ comments

‘Pauses history’s accretion of half-truths and delivers our cherished classics back to us, alive with a new muse.’ — Guardian

‘Twisting out of the grip of Lawson’s original in surprising ways, The Drover’s Wife is a potent piece of storytelling … Some of it is not easy to watch, but Purcell makes it impossible to look away.’ — Sydney Morning Herald

‘Purcell has embraced the full violence and terror of Lawson’s frontier myth, as well as the violence and terror he never would have committed to words … This might be the most important new Australian play written this year, questioning how we tell and respond to the stories of our nation’s past … It will knock the wind out of your sails, and you’ll be glad that it did.’ — Daily Review

‘Beautifully written, thoughtfully made, persuasively performed, and infused with the raw emotion of lived experiences … The entire post-settlement history of Australia has been collapsed into an act of theatre.’ — TimeOut

To Amanda Florence Faith

Writer’s Note

Like many Australians, I’ve grown up with this story and love it. My mother would read or recite it to me, but before she got to that famous last line, I would stop her and say, “Mother, I won’t ever go a drovin’.”

I always wanted to do something with this story with me in it as the drover’s wife. There were two forms of inspiration that motivated me to write this play. First came the film idea in 2006, which I wanted to shoot in the Snowy Mountains. That inspiration came when I was filming the feature film Jindabyne, directed by Ray Lawrence. Secondly, I was in a writing workshop. I was there as a director, but got frustrated. So I went home and said it was time to write my next play. I looked at my bookshelf and there it was: my little red tattered book of Henry Lawson’s short stories. The red cover had now fallen off, its spine thread fraying and my drawings inside as a five-year-old fading.

In the original story, the drover’s wife sits at the table waiting for a snake to come out of her bedroom, having gotten in via the wood heap, which a ‘blackfella’ stacked hollow. While she waits for the snake, she thinks about her life and its hardships. Her oldest son joins her and she shares her story with him.

This is not my version of The Drover’s Wife.

I was heavily influenced by the original story. But I’ve activated all the characters. In my version, I have brought them to life for the stage and reinvented the conversations and action that might have taken place. Weaving my great-grandfather’s story through the play has given it its Aboriginality so to speak, and I’ve embellished the story to give more depth and drama for the stage.

When I did sit down to start writing, the one thing I was conscious of was wanting to apply the stories of the men from my family. By this, I mean taking various positive traits from a particular family individual or a story, and embellishing the characters of Yadaka, Danny and the father of the drover’s wife with these details.

In Henry Lawson’s story, the black man is painted as the antagonist. I thought I would turn that around in my play and have our black man as the hero. With this in mind, I was very conscious of the harshness and brutality of this time. Henry Lawson’s short stories, where ‘The Drover’s Wife’ appears, was first published in 1893. This year was also significant because of an event in my great-grandfather’s life that brought him to Victoria from far north Queensland, which you will hear about in the play.

In one of my earlier drafts, I wasn’t happy with the ending and my partner said, “If we as blackfellas can’t tell the truth of our history, then who can?” This opened up the floodgates, and I wrote like I was riding a wild brumby in the Alpine country, and no apology for the rough ride.

I think of this play as an Australian Western for the stage. I was influenced by the HBO series Deadwood and the Quentin Tarantino film, Django Unchained. I was also influenced by the history that was taken from my great-grandfather’s personal papers, and the recorded history that was documented by people of authority at this time.

This play has been described as dangerous. I love that it is, and give no apology for it. It is also a romance and a story of a mother’s love.

So saddle up and hang on. We are going to come roaring down that mountain, side hit them low flats and rip onto the stage. “Hip’im Jackson!” as my mum would say.

A massive thank you to the Balnaves Foundation for the 2014 award I received to help bring this play to fruition. I also want to thank Eamon Flack for commissioning my play’s premiere season. It was the first play he programmed as Artistic Director at Belvoir, allowing me to continue my 20-year working relationship there as an actor, writer and director… It means a lot. Such a lot. Thank you.

Thank you to the amazing and very talented people involved in the first production of The Drover’s Wife. To the cast for their hard work, knowledge and dedication in bringing the characters to life under the brilliant direction of Leticia Cáceres. Thanks to Leti who brought together a team of generous experts with gentle souls – Stephen Curtis, Tess Schofield, Verity Hampson and Pete Goodwin. Thanks to the wonderful, smart and lovely ladies in stage management, Isabella Kerdijk and Keiren Smith.

To Uncle Hans Pearson and Sean Choolburra of the Guu

gu Yimithirr, and Paul House, Custodian of the Ngambri Walgalu, a huge thank you and much respect. To my elders Aunty Honor Cleary and Uncle Michael Mace for your permission and support. Acknowledging Nana Hazel Mace, Uncle Michael Mace, Francis Adkins, and Lynelle Minnie Mace for your research into our family history.

I must thank my partner in business and in life, Bain Stewart. He is always there and his words of wisdom come at the right time… I fear nothing knowing he is by my side.

To my grandchildren, Wurume Rafael and Lysander Wahn, and our little Sydney silky terrier Odi: thanks for keeping Nan real.

To my daughter Amanda for putting up with me for far too long.

Thanks to my mum for giving me this story and so much more.

With great respect and appreciation to my ancestors for the stories and the ancient ancestors for their guidance.

Altjeringa yirra Baiame.

Leah Purcell

2016

Director’s Note

The Drover’s Wife is a postcolonial and feminist re-imagining of Henry Lawson’s short story by the same name. Leah unapologetically claimed this much-loved frontier narrative and infused it with First Nations and Women’s history, calling into question the shameful treatment endured by both, at the hands of white men. Brutality reels through the writing. Yet this is a work that is steeped in beauty and humanity. Leah’s images, her metaphors, her meticulously crafted characters, her interplay between action, humour and drama, come together to deliver theatre at its most potent. What’s most exciting about Leah’s Drover’s Wife (TDW) is her command of genre – the Western – its tropes so familiar, yet Leah manages to reinvigorate them so we can bare witness to the atrocities of the past from the perspective of those who have been silenced.

For me, the process of directing TDW was primarily about serving Leah’s vision and meeting her bravery. I was determined not to get in the way of her truth. I was guided by the voices of our First Nation artists and Consultants who deepened my understanding of the inhumanity and degradation that has scarred this land.

Finding the theatrical language to stage these abuses was perhaps the most challenging aspect of directing this work. As we rehearsed some of these scenes, at times it felt like our own humanity was being tested. What kept us going was the sense of unity in our rehearsal room; the tenacity with which the entire team (creatives and actors) rallied together to tell this most urgent of stories, and the subversive power of Leah’s writing.

I want to thank Eamon Flack and the Belvoir team who showed outstanding commitment to this project. Belvoir has to be commended for demonstrating genuine and ongoing commitment to telling stories by First Nation artists. These plays have continuously proven they have great power to entertain, but more importantly, to raise the difficult questions of this country’s past, present and future. It is through these works of art and in the act of programming them where reconciliation can take shape, and in turn, how culture will be transformed.

I want to thank TDW’s team. Firstly the cast: Mark Coles Smith, Will McDonald, Tony Cogin and Benedict Hardie. Without their unwavering commitment, we would not have been able to strike the same chord with our audiences.

The creatives: Anthea Williams, who dramaturged TDW with great skill in care; designer Stephen Curtis who asked the hardest theatrical questions; costume designer Tess Schofield, whose every stitch was a stab at patriarchy; lighting designer Verity Hampton for her impeccable attention to detail; composer Pete from THE SWEATS for his ingenious weaving of Leah’s vocal talent; movement director Scottie Witt who helped us depict violence with careful consideration for both actors and audience; Jennifer White, voice coach, for helping us create the tapestry of voices of the frontier. And of course, stage mangers Bella Kerdijk and Keiren Smith who worked tirelessly so we could give the best of ourselves to this production.

I also wish to thank Oombarra Productions, and in particular, producer Bain Stewart who needs to be recognised as instrumental in the success of this work. Oombarra’s contribution by way of expertise, consultancy, advocacy and networks guaranteed that we were always given the best advice, and that we were adhering to all cultural protocols.

But mostly, I want to thank Leah Purcell, who is simply phenomenal. It is through her that I learned the true meaning of courage and respect.

Thank your for your faith in me.

Always was

Always will be

Aboriginal land.

Leticia Cáceres

2017

Leticia Cáceres is a multi-award winning freelance stage director, with a passion for Australian writing. She is based in Melbourne.

Introduction

Artists have always had a critical role in reflecting and influencing the culture of their times. However, as in life, we often only see the dominant aspects of the culture reflected in art. The small voices or dissident voices struggling to rise above the din.

In Henry Lawson’s original version, he reaches out and gives voice to the women of colonial Australia. A voice hitherto barely heard. A whisper. But the story of stoicism and fortitude in the face of abject loneliness and hardship struck a chord and was almost singlehandedly responsible for the creation of an archetype. The image of those women as vulnerable but refusing to surrender – perhaps because there is no choice – had a resonance that was reflected in images such as Frederick McCubbin’s triptych The Pioneer (1904). The image has stuck.

These were the very visions upon which the modern Australian self- image has been built. These images were the precursor to the heroes of Gallipoli and Villers-Bretonneux. in the First World War. The newly formed federation of Australia, along with a new national parliament, developed a new national identity.

The contrast between the colonial portrayal of hard working stolid individuals surviving in a hostile and unforgiving landscape, and the ancient and loving connection of Aboriginal people with our ancestors and country, could not be more stark.

‘Sinister’ is a harsh word. But is there a better word in the English language to describe the fondness for a demonstrably romanticised image of colonial Australia that conveniently forgets our Aboriginal ancestors were being massacred and forcibly removed from our lands? It does not require much imagination to wonder what became of the Aboriginal people who ought to have also been in McCubbin’s triptych, or in Lawson’s ‘The Drover’s Wife’.

Indeed, we do not need tax our imagination. Frederic Urquhart, employed by the Queensland Police to lead the Native Troopers into battle against the Kalkatungu (Kalkadoon) people near Mount Isa in 1884 told us in a poem:

Grimly the troopers stood around

that newly made forest grave

and to their eyes that fresh heap mound

for vengeance seemed to crave.

And one spoke out in deep stern tones

and raised his hand on high

For every one of these poor bones

a Kalkadoon shall die.

For many Aboriginal people that period and the developing Australian identity is a source of deep and unresolved pain. It is here that the artistry and bravery of Leah Purcell’s re-imagining takes a stand. The sheer audacity of taking that most iconic image of the drover’s wife and turning a variety of assumptions on their heads is as wonderfully subversive as it is an act of defiance.

Prior to seeing the play I had wondered how Purcell was going to deal with the lead role of the drover’s wife. I had seen the advertisements showing her dressed in the clothes of the period. It made me feel edgy. Uncomfortable. It was the same discomfort that makes many period dramas unwatchable for Aboriginal people. Reliving the injustice of those times is sometimes unbearable. Historical portrayals in which Aboriginal people have magically disappeared, been erased or have simply been forgotten are only slightly more palatable.

The lead character in this play is the archetype. She is stoic and tough. But as the layers of the character are peeled away we are given insight into the fears, the loneliness of a woma

n alone in the ‘outback’. We see the brutality and inhumanity of colonial Australia as all-but-lawless land. The reality of colonial Australia has been described many times but brought to life in the character of the drover’s wife it is extremely confronting. Her fears are not unfounded.

The supporting character of the eldest son Danny seems to be not only the literal extension of his mother but also a metaphorical tendril reaching out to connect branches of her life. His innocence and curiosity initially masks a deeper relationship to the Aboriginal intruder who arrives in the opening scene. In the final scene when mother and son make good their escape, we hope, calling on almost forgotten stories to guide them out of unbearable and unjust circumstances to which they had fallen in what seems to have been a very short space of time.

It is tempting to read into the script a commentary on the fragile existence of Aboriginal people in the colonial society. Indeed, in this regard, were such insights intended to be laid bare, the colonial Australia of the 1890s does not differ too much from that of the 2010s. The author knows as well as most other Aboriginal people that our success is tolerated, but should we get too uppity or slip up, the privilege of mainstream white recognition will be withdrawn in an instant.

But, as tempting as it is, it is likely that the tolerance afforded to the drover’s wife, of which there is not a lot to start, is ultimately violently stripped away because she is a mere woman.

The subversive nature of this work is readily appreciable. It co-opts a mainstream Australian historical icon and prompts a question as to what others icons of white Australia have a black history. The defiance oozing from this piece is not so readily accessible but it is there to see for those who will look.

In modern Australia Aboriginal stories are most often relegated to the fringe. In this play the author has not only stood her ground and confronted the seemingly immovable object, but challenged it to try to and knock her down. It is conceivable that this re-imagining one of the few cultural pillars of this very young country could have been crushed under the unflinching adherence to cultural dogma that is a hallmark of our nation’s insecurity. So unwilling is our nation to examine the realities of British invasion of the continent, that an assault such as this could have easily been cast as having gone that one step too far.

The Drover's Wife

The Drover's Wife